| Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway |

The Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway is the 17.3 miles of I-95 and I-395, from near Woodbridge, Virginia, to the south end of the 14th Street Bridge which carries I-395 into the District of Columbia.

Article index with internal links

Introduction

Henry G. Shirley - Commissioner of Virginia Department

of Highways

Shirley Highway Early History

Pentagon Road System

Summary of Original Shirley Highway Openings

Shirley Highway in the 1950s - Early Years of Completed Highway

Shirley Highway in the 1960s - Planning and Beginning the

Reconstruction

Transfer of Pentagon Road System From Federal

Government to Virginia

Shirley Highway Today

Sources

Links to External Websites

Links to My Website Articles

Acronyms

Credits

Virginia's first limited access freeway, the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway, was completed from Woodbridge, Virginia to the 14th Street Bridge over the Potomac River, in 1952, and it was 17.3 miles long. The road was a four-lane freeway, and it was designated Virginia Route 350 from US-1 at its south end to US-1 near the Pentagon Building, and the highway was designated US-1 on its northernmost 0.7 mile; and the 14th Street Bridge was also designated US-1. Shirley Highway was named after the Virginia Department of Highways commissioner (agency head) who died in July, 1941, just a few weeks after giving the "go ahead" for work on the new freeway. The section in Arlington was opened in 1944, at the time the Pentagon (War Department Building) was completed. This section included the Mixing Bowl interchange complex near the Pentagon with VA-27 and the Pentagon parking lots. Shirley Highway was designated as Interstate 95 as projects were completed as it was reconstructed to Interstate standards from 1965 to 1975, with the 13 miles from US-1 near Woodbridge to VA-7 King Street being completed by 1968, and the remainder from VA-7 to the 14th Street Bridge being completed by 1975.

Interstate 395 in Virginia runs for 9.6 miles, from the I-95/I-495 Capital Beltway at Springfield to the 14th Street Bridge Complex (I-395 and US-1) over the Potomac River. This highway was originally I-95, and it was redesignated I-395 in 1977 because of the rerouting of I-95 to the eastern half of the Capital Beltway, done because of the cancellation of proposed I-95 from New York Avenue in the District of Columbia, northward into Prince George's County to the I-495 Capital Beltway. I-395 continues in D.C. up to New York Avenue.

The southern end of the original Shirley Highway had a high-speed wye interchange with US-1 about 0.8 mile north of the Occoquan River, which is just north of Woodbridge. I-95 was completed from Fredericksburg to the south end of Shirley Highway in 1964, with I-95 joining Shirley Highway at what is today's Exit 161. Actually, a section of the original beginning of the 2-lane northbound Shirley Highway roadway, about 1/3-mile-long, unwidened and nearly in its original state with the concrete pavement overlaid with asphalt, still exists as the northbound onramp from US-1 northbound to I-95 northbound.

Shirley Highway was reconstructed to urban interstate standards from 1965 to 1975, at a cost of $162 million. The number of lanes ranged from six lanes near Woodbridge to twelve lanes at the 14th Street Bridge, with a maximum of 18 lanes in the Mixing Bowl. During the reconstruction, in 1969, a reversible exclusive busway was opened, allowing express bus traffic in the rush-hour direction of traffic. This was the first such facility on a freeway in the nation. As mentioned before, I-95 inside the Beltway was redesignated I-395 in 1977. The reversible 2-lane HOV roadway runs from just south of the VA-644 interchange at Springfield to near the Pentagon where it divides into a northbound and southbound pair of 2-lane express roadways between there and the Southeast Freeway and 14th Street in the District of Columbia. The 2-lane reversible HOV roadway runs the whole length of Shirley Highway today, with I-95 widening projects having extended the HOV roadway from Springfield to Dumfries, completed in sections in a southward sequence from November 1994 to June 1997.

The Mixing Bowl Interchange Complex near the Pentagon was rebuilt from 1970 to 1973, as part of the reconstruction of Shirley Highway. The original Shirley Highway was a four-lane freeway. The Mixing Bowl interchange is where the VA-27 freeway (Washington Blvd.) merges with Shirley Highway and then branches off again. The original interchange had a merge section each way, about 1/3 mile long, with a third "mixing lane" where the vehicles would weave when they wanted to change to the other freeway. By the late 1960s, it was a severe bottleneck during rush hour. The rebuilt interchange has the same conceptual movements, but the weaves take place on grade-separated semi-directional ramps. It is a massive interchange. One cross-section point has 27 lanes on three levels and 10 separate roadways. Eliminating non-freeway parts of the cross-section, the facility is 18 lanes wide. The Mixing Bowl includes not just the weave section between I-395 and VA-27, but also interchanges with the Pentagon parking lots (which are huge) and Pentagon City, and with VA-244 Columbia Pike. Not directly related to the highway, but in the Mixing Bowl project, the WMATA Metrorail subway tunnel was built under Shirley Highway, for the Huntington Route (Blue Line and Yellow Line trains) near where Hayes Street junctions with Army-Navy Drive. That segment of Metrorail opened to passenger service in July 1977.

According to an Engineering News-Record feature article in 1973, the rebuilt Mixing Bowl comprised the largest interchange complex in the world. A 2-1/2 mile section of Shirley Highway has 52 lane-miles of roadways and ramps, with four freeway junctions and numerous local ramps, and with several interchanges to the reversible express (HOV) roadway on Shirley Highway. I don't think that there are any larger interchange complexes built since then. [30]

See my article

Mixing Bowl Interchange Complex for aerial photos

of the Mixing Bowl. VDOT photo rendering above.

See "The Mixing Bowl Project (1970-1973)", and "The Pentagon Building (1941-1943)", from The History and Heritage of Civil Engineering in Virginia, by J.C. Hanes and J.M. Morgan, Jr., 1973, Virginia Section of American Society of Civil Engineers.

See my article Shirley Highway Busway/HOV System for a detailed Virginia Highway Bulletin July 1974 article about the busway/HOV system and the highway reconstruction.

"Springfield Interchange" - Not "Mixing Bowl"

The current Springfield Interchange Project involves reconstructing what is actually two interchanges: 1) The interchange between Shirley Highway and the Capital Beltway. Shirley Highway is I-95 south of the Beltway, and is I-395 north of the Beltway. The Capital Beltway is I-495 throughout, and carries I-95 also east of Shirley Highway. 2) The interchange between I-95 Shirley Highway and VA-644. VA-644 is Franconia Road east of I-95 and is Old Keene Mill Road west of I-95.

The current 8-year, 7-phase Springfield Interchange construction project began in March 1999 and is on schedule for completion in 2007. On this project, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) is the administrator of the planning, design, right-of-way acquisition and construction. Throughout their literature, they use the name "Springfield Interchange Project" or "Springfield Interchange Improvement Project" to denote the name of this project. The name "Mixing Bowl" has been widely used recently in the local media for this interchange and project. VDOT only very occasionally uses that name, and for good reason -- the Mixing Bowl is the historic name for the interchange between I-395 Shirley Highway and VA-27 Washington Boulevard in Arlington, Virginia, near the Pentagon. The Mixing Bowl interchange is where the VA-27 freeway (Washington Blvd.) merges with I-395 and then branches off again. For more details, see my aforementioned website article "Mixing Bowl Interchange Complex", and the aforementioned Virginia Section of American Society of Civil Engineers article "The Mixing Bowl Project (1970-1973)", from The History and Heritage of Civil Engineering in Virginia, by J.C. Hanes and J.M. Morgan, Jr., 1973. The "Mixing Bowl" name was applied to this interchange as far back as 1943 when it was originally opened, and I find it absurd that just in the last few years the local media has started calling another interchange just 8 miles away by the same name! Having two interchanges so close to each other, with each having the same name, is illogical and nonsensical. The Mixing Bowl name has never been removed from the I-395/VA-27 interchange, as far as I know. Henceforth, I refuse to use that name for the I-95/I-395/I-495 interchange -- I will call it the "Springfield Interchange" throughout this article and anywhere else it is mentioned on this website.

Henry G. Shirley - Commissioner of Virginia Department

of Highways

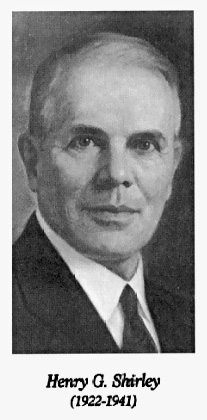

Henry Garnett Shirley was the Commissioner

(agency head) of the Virginia Department of Highways (VDH), from 1922 until his

death in July 1941. His 19-year tenure is the longest of any of the 14 Commissioners

in the history of VDH/VDOT which began in 1906. He served under five different

governors and is credited with leading the Department of Highways through many

of its critical early years when the state primary highway system was being built

as modern paved motor vehicle roads, and when much of the state secondary highway

system was being modernized to carry motor vehicles and to “get the farmers out

of the mud” (the old unimproved secondary roads often turned to mud after a heavy

rain).

|

Photo from A History of Roads

in Virginia "The Most Convenient Wayes", 2002, page 46, Virginia's

Highway Commissioners, Virginia Department of Transportation. Here is a

cite of what one of his contemporaries (the division administrator of the

Location and Design Division of the Virginia Department of Highways) wrote

about him in 1946 (blue text):

The Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway will be Virginia’s

first example of a modern Express Highway with controlled access, and was

named by Act of the Commission in March, 1942, for the late beloved Henry

G. Shirley, first President of the American Association of State Highway Officials,

and Highway Commissioner of Virginia from 1922 until his death in July 1941.

[2] Another cite from the Virginia Road Builder, “The Shirley Memorial Highway”, July-August 1950, (blue text): The expressway is named in memory of the late Henry G. Shirley, who died in 1941 after serving for 19 years as Virginia’s Highway Commissioner. During these 19 years, Virginia raised the standards for her roads, building them on a “pay-as-you-go” basis until she became the envy of her sister states. Only a few weeks before his death, Mr. Shirley gave the “go ahead” for work on this expressway, in order to prepare Virginia for the threatened war. [8] |

A History of the Commonwealth

Transportation Board, by the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT),

1986, has this biography of Henry G. Shirley (blue text):

Henry G. Shirley (1922-1941)

Henry G. Shirley was first appointed

by Governor E. Lee Trinkle and also served under Governors Harry F. Byrd, John

Garland Pollard, George C. Peery and James H. Price. He saw the need for an advanced

highway plan leading through the Virginia suburbs to Washington, D.C., and under

his direction, work began on the first limited access road in the state. Now known

as the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway, the road, which is part of I-95 and

I-395, extends from Route 1 in Northern Virginia to the 14th Street Bridge in

Washington, D.C. Shirley held a position as professor of military science at Horner

Military School in Oxford, N.C. After serving in the Spanish-American War, he

worked for the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad and other railroad companies

and served with the engineering department of the District of Columbia. He was

roads engineer for Baltimore County, Md., and chief engineer of the Maryland State

Roads Commission. During World War I, he served on the Highway Transport Committee,

Council of National Defense, helping keep the roads of the nation in shape to

handle military traffic. In 1918, he was named executive secretary of the Federal

Highway Council, and in 1920 served once more as engineer of Baltimore County.

A native of Locust Grove, W.Va., he graduated from Virginia Military Institute

in 1896 with a civil engineering degree and later from the University of Maryland

with a doctor of science degree. He died in office in 1941.

[32]

FHWA By Day, September 6, 1949,

excerpt (blue text): Extension of the Shirley Memorial Highway -- a 17-mile, four-lane expressway -- opens from a point south of the Pentagon highway network to Woodbridge, VA. The highway is named for the Virginia Highway Commissioner Henry G. Shirley, who died on July 16, 1941, just a few weeks after giving the "go ahead" for work on the expressway.The above citations don't give Mr. Shirley's birth year, but if he was at least 22 years old when he graduated from VMI, that would make him at least 67 years old when he passed away. Interestingly, I've never seen any writings that referred to him as "Dr. Shirley", despite the fact that he had a doctor of science degree from the University of Maryland. His possessing a civil engineering degree from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) follows a pattern that many of the civil engineers at VDH/VDOT have followed.

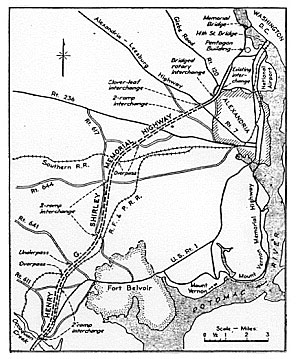

Originally known as the Fort Belvoir

Bypass during preliminary planning in the 1930s, this 17.3-mile-long highway was

conceived as a bypass of US-1 Jefferson Davis Highway, from just north of Woodbridge,

to the Highway Bridge which carried US-1 over the Potomac River into the District

of Columbia (D.C.) onto 14th Street. The highway would bypass Mount Vernon, Fort

Belvoir and downtown Alexandria, passing through what was then almost all open

and undeveloped land, and would be 2.4 miles shorter than the pre-existing route

on US-1. The original name of what is now known as the 14th Street Bridge,

was the Highway Bridge, and it was a single old 4-lane steel truss bridge back

then, which was later eliminated after a replacement span was opened in 1962.

The new highway’s traffic would be carried into and out of D.C. on the Highway

Bridge. In 1940, the U.S. Public Roads Administration and the Virginia Department

of Highways jointly established a tentative route for the Fort Belvoir Bypass,

similar to what was eventually built. [10, 1]

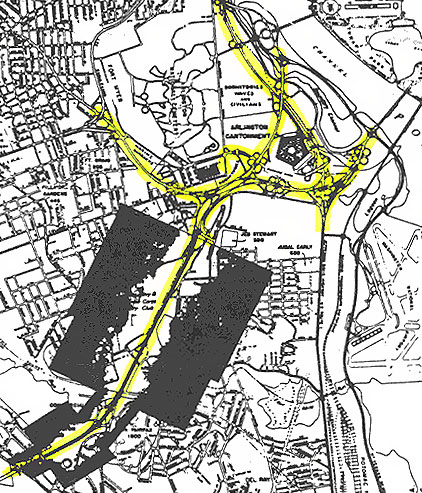

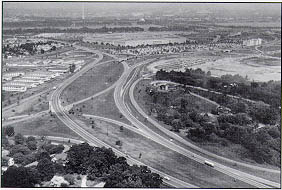

The construction of the War Department Building (later named the Pentagon) in Arlington in mid-1941 is what directly led to the start of actual construction of the first section of Shirley Highway in that part of Arlington, to facilitate the existing heavy traffic in that part of Arlington, as well as the projected volumes of commuter traffic to and from the Pentagon Building which was projected to have over 20,000 employees almost immediately upon opening. The first section of Shirley Highway to be built was the section from VA-7 Alexandria-Leesburg Highway to the Highway Bridge, and the U.S. Public Roads Administration (PRA) directly administered the design, right-of-way acquisition and construction of this 4-mile-long section of highway which was designed to full freeway standards with a total of 4 lanes, 2 lanes each way with a grass median dividing the two roadways, with space for future 6-lane widening. Interchanges were built at VA-7, Quaker Lane, Glebe Road, Arlington Ridge Road, Washington Boulevard, the Pentagon South Parking Lot, Jefferson Davis Highway, Boundary Channel Road, and George Washington Parkway. The western branch of Washington Boulevard, and the eastern branch of Washington Boulevard to Arlington Memorial Bridge over the Potomac River, were both built at the same time as was this section of Shirley Highway. This section of Shirley Highway was built from 1941 to mid-1943, with the Shirley Highway portion being opened then, but the last element of the complex wasn’t completed until 1952.

|

Photo image of the

original Shirley Highway in the Pentagon area. The Mixing Bowl interchange

with VA-27 Washington Boulevard is in the middle of the photo, and the Pentagon

is in the background, and the Potomac River and the Washington Monument is

in the distance. Photo by U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, 1954. |